Try GOLD - Free

What to Make of Miracles

The Atlantic

|May 2025

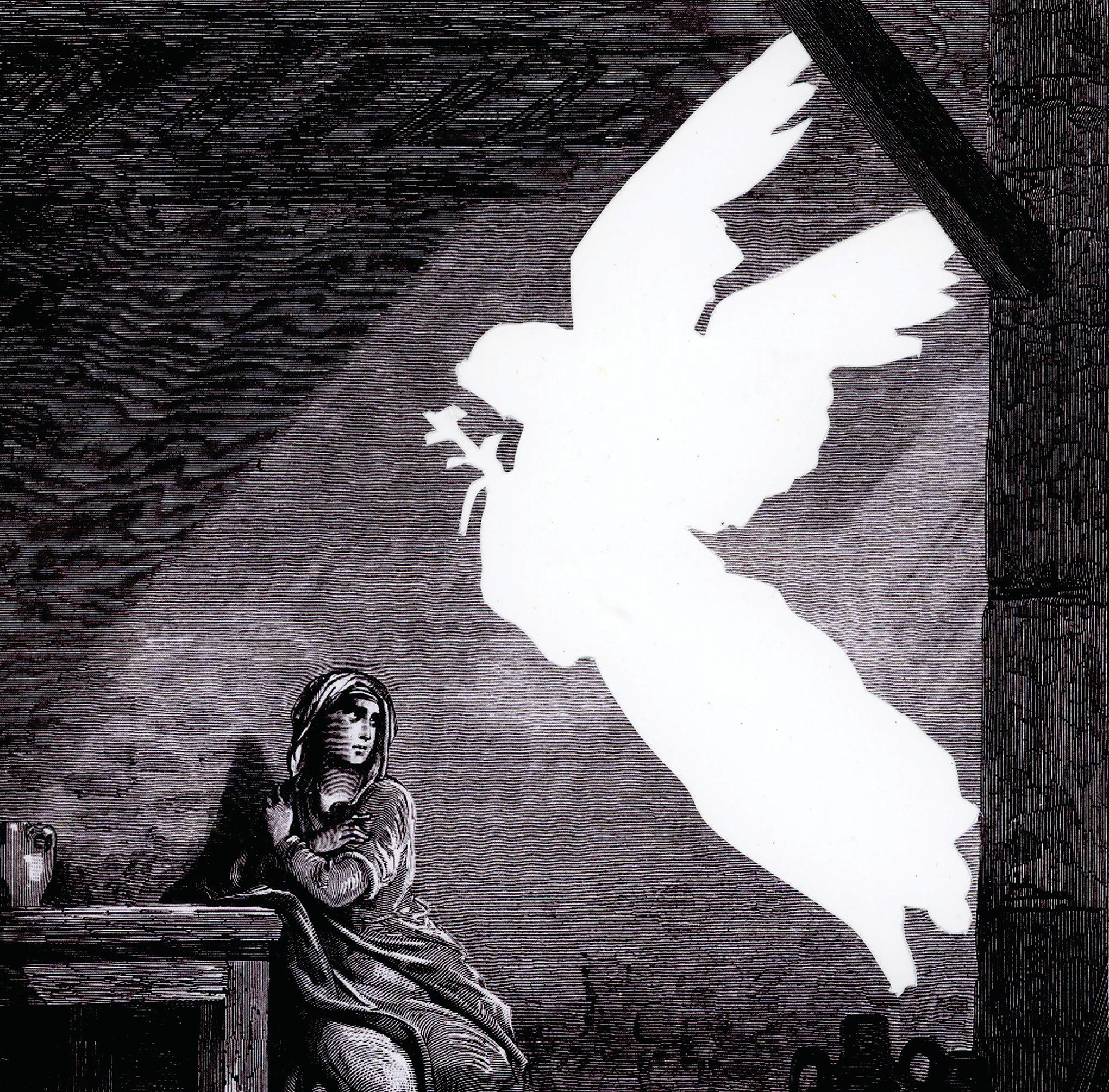

In a new book, Elaine Pagels searches for the narrative origins of Jesus's most wondrous acts.

How should we understand miracles? Many people in the near and distant past have believed in them; many still do. I believe in miracles too, in my way, reconciling rationalism and inklings of a preternatural reality by means of “radical amazement.” That's a core concept of the great modern Jewish philosopher Abraham Joshua Heschel. Miracles, insofar as Heschel would agree with my calling them that—it’s not one of his words—do not defy the natural order. God dwells in earthly things. Me, I find God in what passes for the mundane: my family, Schubert sonatas, the mystery of innate temperament. A corollary miracle is that we have been blessed with a capacity for awe, which allows us “to perceive in the world intimations of the divine, to sense in small things the beginning of infinite significance,” Heschel writes.

Every so often, though, I wonder whether radical amazement demands enough of us. Heschel would never have gone as far as Thomas Jefferson, who simply took a penknife to his New Testament and sliced out all the miracles, because they offended his Enlightenment-era conviction that faith should not contradict reason. His Jesus was a man of moral principles stripped of higher powers. But a faith poor in miracles is an untested faith. At the core of Judaism and Christianity lie divine interventions that rip a hole in the known universe and change the course of history. Jesus would not have become Christ the Savior had he not risen from his tomb. Nor would Jews be Jews had Moses not brought down God's Torah from Mount Sinai.

What problems did the miracle stories solve; what new vistas did solving them open; what religious function did they serve?

This story is from the May 2025 edition of The Atlantic.

Subscribe to Magzter GOLD to access thousands of curated premium stories, and 10,000+ magazines and newspapers.

Already a subscriber? Sign In

MORE STORIES FROM The Atlantic

The Atlantic

You Had to Be There

An emerging field of history asks if we can ever really understand how our forebears experienced love, anger, fear, and sorrow.

23 mins

January 2026

The Atlantic

By the Horns

The week before the biggest bullfight of her career, in Cádiz, Spain, this past July, 24-year-old Miriam Cabas posted a carefully produced video on Instagram.

1 mins

January 2026

The Atlantic

The New German War Machine

After World War II, Germany embraced pacifism as a form of atonement. Now the country is arming itself again.

18 mins

January 2026

The Atlantic

The Eloquence

The prime minister was watching a disaster movie when we found him.

4 mins

January 2026

The Atlantic

What's for Dinner, Mom?

The women who want to change the way America eats

12 mins

January 2026

The Atlantic

How Terror Works

A 1947 German novel explores the sometimes corrosive, sometimes energizing nature of fear.

8 mins

January 2026

The Atlantic

Yesterday's Idea of a Modern Man

Sam Shepard, a self-made cowboy, was also a poet of masculine angst.

7 mins

January 2026

The Atlantic

ACCOMMODATION NATION

America's colleges have an extra-time-on-tests problem.

11 mins

January 2026

The Atlantic

Respect the Drummer

A new history of rock, told through its overlooked heroes

5 mins

January 2026

The Atlantic

THE MOST POWERFUL MAN IN SCIENCE

WHY IS ROBERT F. KENNEDY JR. SO CONVINCED HE'S RIGHT?

42 mins

January 2026

Listen

Translate

Change font size