Versuchen GOLD - Frei

The Forgotten Still-Life Prodigy

The Atlantic

|September 2025

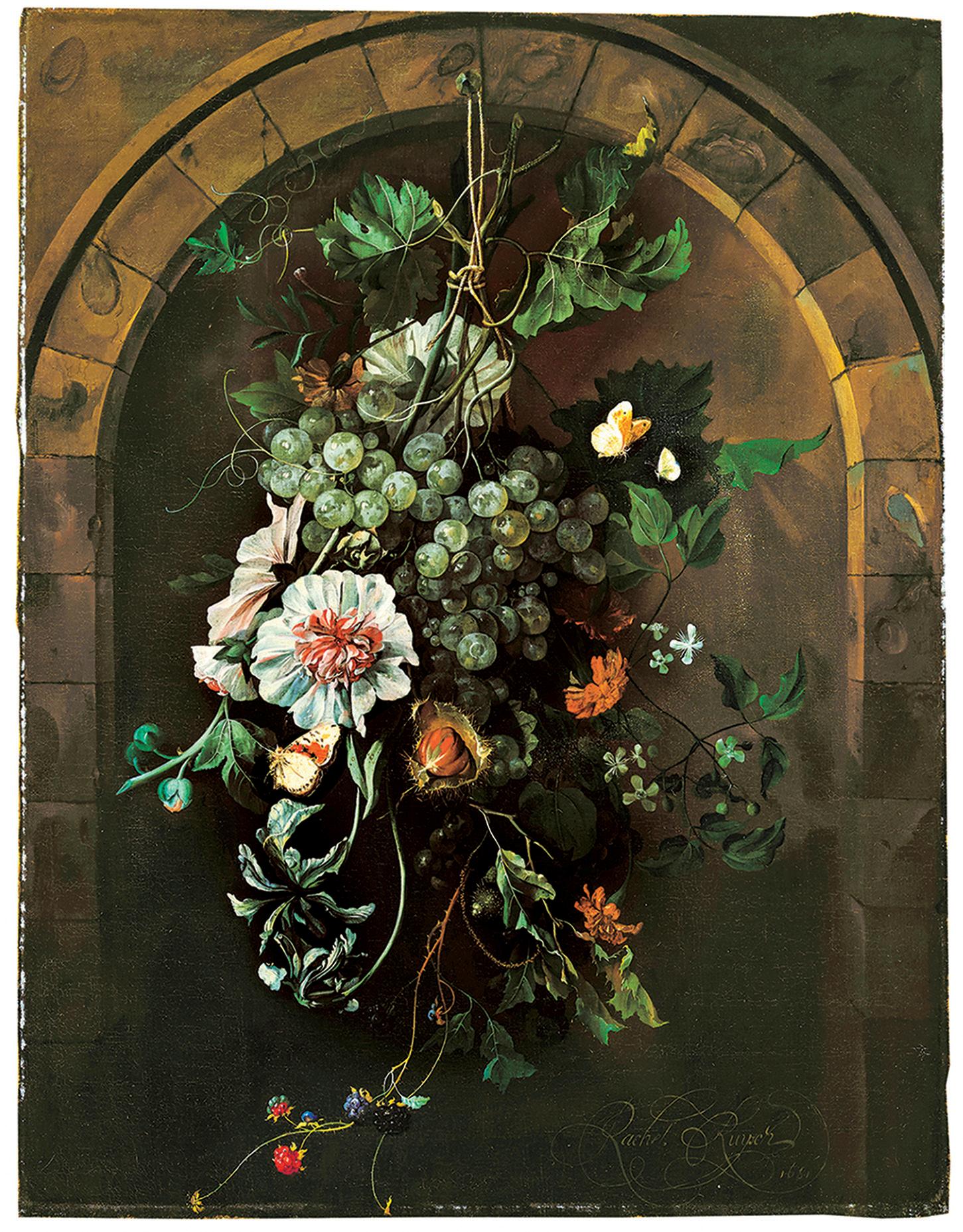

The 17th-century painter Rachel Ruysch was once more famous than Vermeer.

If still-life painting is the art of arresting decay, then it makes a lot of sense that Rachel Ruysch grew up to become one of the greatest still-life painters in the history of art. In the 17th century, Frederik Ruysch, her father, was an internationally famous embalmer. His job was to make a natural object seem permanently alive and pleasing to the eye. He could transform the corpse of a bullet-pierced admiral into the “fresh carcase of an infant,” Samuel Johnson once said. He could turn dead children into the serenest version of themselves—their faces so full of life that people wanted to kiss them, as Peter the Great once did.

The house where Rachel grew up, near the town hall in Amsterdam, had an annex for her father's skeletons, organ jars, and severed limbs, which he collected along with a growing stockpile of dead insects, amphibians, and flowers. It was a rich soil in which to live and work if you were an ambitious Enlightenment-era man of science, as Frederik was. To be a child in that environment, though, would have been incredibly weird. Imagine your father coming home day after day smelling of organ meat, his clothes speckled with blood and vague fluids. He keeps trying to show you his newest cow's heart or amputated foot, or a skink shipped in from one of the colonies. What's that under the chair? Ah, yes—a piece of lung. The barrier between life and death starts to seem thinner, more porous. Your sense of beauty dilates and shifts.

Rachel Ruysch (1664-1750) did not spend her time dissecting stray dogs or making fake fiddles out of human thigh bones, as her father did. Instead she devoted herself to the most conventionally beautiful object in nature: the flower. In fact, she became one of the top flower painters in Europe. Even though Ruysch is now a footnote in art history, she was more famous in her own lifetime than Rembrandt and Vermeer.

Diese Geschichte stammt aus der September 2025-Ausgabe von The Atlantic.

Abonnieren Sie Magzter GOLD, um auf Tausende kuratierter Premium-Geschichten und über 9.000 Zeitschriften und Zeitungen zuzugreifen.

Sie sind bereits Abonnent? Anmelden

WEITERE GESCHICHTEN VON The Atlantic

The Atlantic

You Had to Be There

An emerging field of history asks if we can ever really understand how our forebears experienced love, anger, fear, and sorrow.

23 mins

January 2026

The Atlantic

By the Horns

The week before the biggest bullfight of her career, in Cádiz, Spain, this past July, 24-year-old Miriam Cabas posted a carefully produced video on Instagram.

1 mins

January 2026

The Atlantic

The New German War Machine

After World War II, Germany embraced pacifism as a form of atonement. Now the country is arming itself again.

18 mins

January 2026

The Atlantic

The Eloquence

The prime minister was watching a disaster movie when we found him.

4 mins

January 2026

The Atlantic

What's for Dinner, Mom?

The women who want to change the way America eats

12 mins

January 2026

The Atlantic

How Terror Works

A 1947 German novel explores the sometimes corrosive, sometimes energizing nature of fear.

8 mins

January 2026

The Atlantic

Yesterday's Idea of a Modern Man

Sam Shepard, a self-made cowboy, was also a poet of masculine angst.

7 mins

January 2026

The Atlantic

ACCOMMODATION NATION

America's colleges have an extra-time-on-tests problem.

11 mins

January 2026

The Atlantic

Respect the Drummer

A new history of rock, told through its overlooked heroes

5 mins

January 2026

The Atlantic

THE MOST POWERFUL MAN IN SCIENCE

WHY IS ROBERT F. KENNEDY JR. SO CONVINCED HE'S RIGHT?

42 mins

January 2026

Listen

Translate

Change font size