يحاول ذهب - حر

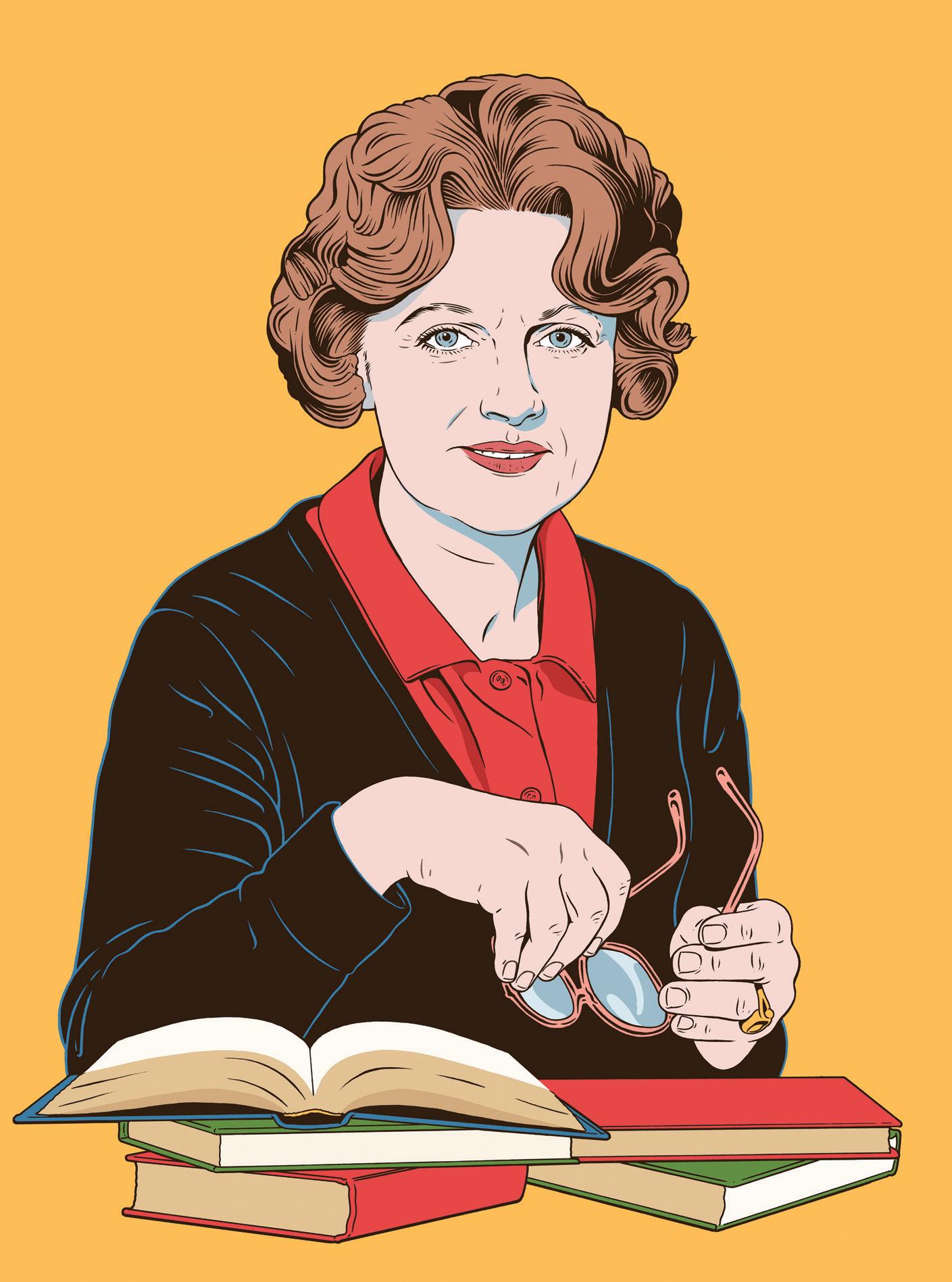

The Judgments of Muriel Spark

September 2025

|The Atlantic

The novelist Muriel Spark died almost 20 years ago, but she still regularly appears on lists of top comic novelists to read on this subject or that. Crave more White Lotus-level skewering of the ridiculous rich? Try Memento Mori, The New York Times suggests. An acerbic take on boring dinner parties? Symposium. Interested in “the fun and funny aspects of being a teacher”? Read The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie— also good for learning how to be a highly inappropriate teacher, if you want to know that too.

Obscured by her reputation as a wit is the fact that Spark was a religious writer—indeed, one of the most important religious writers in modern British literature. She embraced Roman Catholicism in 1954, at age 36, and joined the cohort of renowned literary Catholic converts such as T. S. Eliot, Evelyn Waugh, and Graham Greene. The most consistent influence on her work is the Bible, especially the Old Testament. She began reading it as a girl in her Presbyterian school and kept rereading it throughout her life, less for “religious consolation,” she writes in her essay “The Books I Re-Read and Why,” than “for sheer enjoyment of the literature.” She was particularly drawn to the Book of Job, an anguished outcry against the seeming randomness of evil. And yet her tone throughout her work is so acidly droll, her touch so light and sly, that we could read most of her 22 novels and 41 short stories and never quite process that their central concern is God.

That's because she communicates her theology largely through form rather than content. She rarely discusses; she prefers to sculpt. With a steely command of omniscience, selective disclosure, irony, and other narrative devices, Spark re-creates in the relationship between author and reader the sadomasochistic partnership between the Almighty and his hopelessly wayward flock—or, to put it another way, between his absolute truth and our partial understanding. In other words, she plays God. Not necessarily a nice God, either. In the Book of Job, the Almighty is mercilessly capricious, condemning Job to bitter suffering in a wager with Satan. This God's ends are not our ends. Nor are Spark’s. A Creator who acts according to his will on his own unknowable schedule darkens her bright, chipper prose like a skull in a still life. “Remember you must die,” the anonymous callers in

هذه القصة من طبعة September 2025 من The Atlantic.

اشترك في Magzter GOLD للوصول إلى آلاف القصص المتميزة المنسقة، وأكثر من 9000 مجلة وصحيفة.

هل أنت مشترك بالفعل؟ تسجيل الدخول

المزيد من القصص من The Atlantic

The Atlantic

You Had to Be There

An emerging field of history asks if we can ever really understand how our forebears experienced love, anger, fear, and sorrow.

23 mins

January 2026

The Atlantic

By the Horns

The week before the biggest bullfight of her career, in Cádiz, Spain, this past July, 24-year-old Miriam Cabas posted a carefully produced video on Instagram.

1 mins

January 2026

The Atlantic

The New German War Machine

After World War II, Germany embraced pacifism as a form of atonement. Now the country is arming itself again.

18 mins

January 2026

The Atlantic

The Eloquence

The prime minister was watching a disaster movie when we found him.

4 mins

January 2026

The Atlantic

What's for Dinner, Mom?

The women who want to change the way America eats

12 mins

January 2026

The Atlantic

How Terror Works

A 1947 German novel explores the sometimes corrosive, sometimes energizing nature of fear.

8 mins

January 2026

The Atlantic

Yesterday's Idea of a Modern Man

Sam Shepard, a self-made cowboy, was also a poet of masculine angst.

7 mins

January 2026

The Atlantic

ACCOMMODATION NATION

America's colleges have an extra-time-on-tests problem.

11 mins

January 2026

The Atlantic

Respect the Drummer

A new history of rock, told through its overlooked heroes

5 mins

January 2026

The Atlantic

THE MOST POWERFUL MAN IN SCIENCE

WHY IS ROBERT F. KENNEDY JR. SO CONVINCED HE'S RIGHT?

42 mins

January 2026

Listen

Translate

Change font size