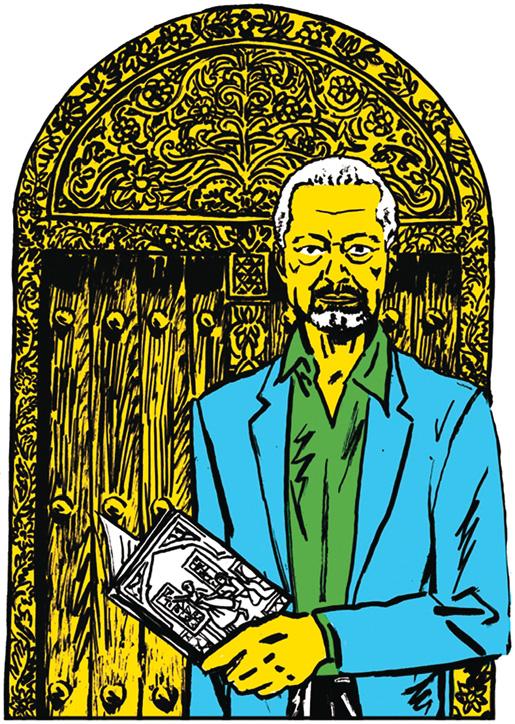

Armies, like writers, prey on orphans and misfits. Scenes of military recruitment have been a literary staple at least since Bulgarian soldiers kidnapped Voltaire's Candide, but few are more bleakly memorable than the one at the end of "Paradise" (1994), by the novelist Abdulrazak Gurnah. It's around the time of the First World War. Yusuf, a runaway servant in what's now Tanzania, wanders into a camp abandoned by askari, or local troops, who have occupied his coastal town in the name of Germany. He finds wild dogs eating the soldiers' excrement, and, when they return his gaze, experiences a shock of recognition. "The dogs had known a shit-eater when they saw one,” Yusuf decides, and promptly joins the askari.

The grotesque analogy poses a painful question: How did so many colonial subjects end up fighting for their conquerors, living, as it were, on the leftovers of empire? More than a million Africans served in the two World Wars, deployed both in Europe and in their own occupied continent. Gurnah, who grew up in Zanzibar, knew that one of his relatives had been conscripted as a porter into Germany’s Schutztruppe. Another had enlisted with the British, in the King’s African Rifles.

Yet scarcely any testimony survived to account for the experiences of soldiers like them. In Paradise,” his lapidary fourth novel, he tried to envision what kind of life might lead to such an act of desertion.

Bu hikaye The New Yorker dergisinin October 24, 2022 sayısından alınmıştır.

Start your 7-day Magzter GOLD free trial to access thousands of curated premium stories, and 8,500+ magazines and newspapers.

Already a subscriber ? Giriş Yap

Bu hikaye The New Yorker dergisinin October 24, 2022 sayısından alınmıştır.

Start your 7-day Magzter GOLD free trial to access thousands of curated premium stories, and 8,500+ magazines and newspapers.

Already a subscriber? Giriş Yap

Thataway Thomas McGuane

The two sisters were growing old now, but they went on gazing toward Palm Springs from this windblown prairie town as though to Mecca.

THE CURRENT CINEMA APOCALYPSE WHEN

“Megalopolis.”

THE THEATRE - PHOTO REALISM

Moisés Kaufman's Here There Are Blueberries.”

AGE OF ANXIETY

The love songs of Billie Eilish.

FAMILY PORTRAIT

In his latest novel, Garth Risk Hallberg shrinks his frame.

EYES UP HERE

The perils and pleasures of a nice rack.

A CRITIC AT LARGE SAY THE WORD

Why liberals struggle to defend liberalism.

A REPORTER AT LARGE YOU MAKE ME SICK

How corporate scientists discovered—and then helped to conceal—the dangers of forever chemicals.

THE WORLD OF TELEVISION CASTOFFS

REALITY-TV CONTESTANTS ARE BARELY PAID, AND THE EXPERIENCE CAN FEEL LIKE ABUSE. SHOULD THEY UNIONIZE?

SHOUTS & MURMURS IDENTIFIED

A panel of scientific experts commissioned by NASA to study unidentified anomalous phenomena,” more widely known as UFOs, said Thursday that it found no evidence that any of the reported objects were extraterrestrial in origin.