Admittedly, the idea of time travel has always given me a smirk. I suppose that is because to me it has always sounded like a fantasy that could never be actualized. Hence, entertaining the idea of its possibility felt like a waste of time. Nonetheless, as I encounter this concept more and more often these days, especially as a part of intellectual conversations and philosophical speculations, I must admit that somehow time travel keeps me wondering. My momentary contemplations, however, do not necessarily focus on whether it is practically possible to travel to a certain point in the past or in the future. Rather, they help me deep dive into the nature of time itself.

Defining time may, at first, seem quite straightforward. After all, we are all familiar with the idea of time in the sense of duration and its measurement. However, what time is in its essence is a much more difficult question, with a long history of philosophical disputes and still no agreed definition.

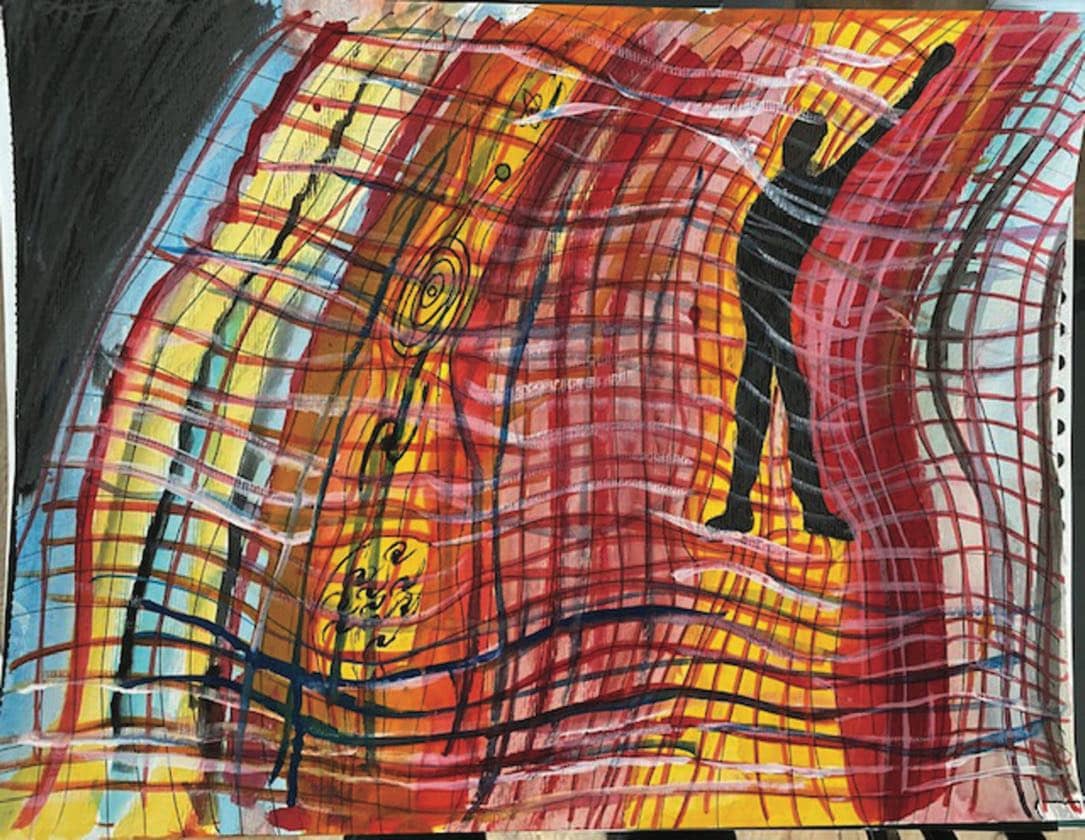

Our most common intuition tells us that time is a passing phenomenon. What this entails is that space (or the physical universe) is in a fixed or static position and time, like a film running through an old projector if you will, comes and passes through the universe. As time comes, it brings all the changes with it. In other words, the universe changes through time.

This story is from the December 2021 / January 2022 edition of Philosophy Now.

Start your 7-day Magzter GOLD free trial to access thousands of curated premium stories, and 8,500+ magazines and newspapers.

Already a subscriber ? Sign In

This story is from the December 2021 / January 2022 edition of Philosophy Now.

Start your 7-day Magzter GOLD free trial to access thousands of curated premium stories, and 8,500+ magazines and newspapers.

Already a subscriber? Sign In

"Stand Out Of My Light"

Sophie Dibben watches Alexander the Great meet Diogenes the Cynic.

Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679)

Hilarius Bogbinder looks at a man who wanted to make Peace from Warre.

The Philosophy of Work

Alessandro Colarossi has insights for the bored and understimulated.

Towards Love

George Mason on love as shared identity.

Hume's Problem of Induction

Patrick Brissey exposes a major unprovable assumption at the core of science.

A Philosophical History of Transhumanism

John Kennedy Philip goes deep into the search for (post-) human heights.

How to Have a Good Life

Meena Danishmal asks if Seneca's account of the good life is really practical.

Horseplay in Hibernia

Seán Moran explores equine escapades in Eire and elsewhere.

Philosophy & Hurling: Thinking & Playing

Stiofán Ó Murchadha knowing how we know.

Philip Pettit & The Birth of Ethics

Peter Stone thinks about a thought experiment about how ethics evolved.