In early June, #BlackInTheIvory went viral on Twitter. Created by Shardé M. Davis, an assistant professor at the University of Connecticut, and Joy Melody Woods, a doctoral student at the University of Texas at Austin, the hashtag asked Black scholars “to share their experience with higher ed institutions.” Academics responded in droves, detailing the myriad ways that Black scholars, scholarship, and excellence have been undermined and undervalued. One person described a colleague remarking that “Blacks have lower IQs than whites,” another reported being told that they were “not really Black because [they] are good.” Scholars were told that they were just “diversity hire[s].” One Black woman received a student evaluation alleging she had committed malpractice by presenting race as central to American history and saying she should never teach again.

That hashtag led to others within the academic community, like #Strike4BlackLives and #ShutDownSTEM — efforts in which non-Black scholars were asked to pause their day-to-day work to reflect on ways of addressing anti-Black racism in their fields. These conversations were a part of the larger reckoning with systemic racism prompted by George Floyd’s murder, a movement that has included protests and calls for widespread change in various industries, including policing, publishing, and news media.

The responses to Davis and Woods’s call tell startling tales of unfiltered workplace hostility and racism. But, to me, they are unsurprising — they are the reality of so many professions and institutions. I have told versions of this story myself.

This story is from the November/December 2020 edition of The Walrus.

Start your 7-day Magzter GOLD free trial to access thousands of curated premium stories, and 8,500+ magazines and newspapers.

Already a subscriber ? Sign In

This story is from the November/December 2020 edition of The Walrus.

Start your 7-day Magzter GOLD free trial to access thousands of curated premium stories, and 8,500+ magazines and newspapers.

Already a subscriber? Sign In

Invisible Lives

Without immigration status, Canada's undocumented youth stay in the shadows

My Guilty Pleasure

"The late nights are mine alone, and I'll spend them however I damn well please"

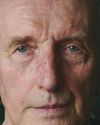

Vaclav Smil Is Fed Up

The acclaimed environmental scientist is criticizing climate activists, shunning media, and stepping back just when we need him most

It's Time for a Birth Control Revolution

What the pill teaches us about the failure - and future - of women's health care

Would You Watch a Play about Hydro Electricity?

How documentary theatre struck a chord in Quebec

Still Spinning

One record chain has bet big on a new appetite for physical media

Just So You Know, I Love My Mother

In many ways, multi-generational living makes sense. But that doesn't make it easy

Art of the Steal

Why are plundered African artifacts still in Western museums?

Canada in the Middle

What role can we play in easing the war in Gaza?

Canadian Multiculturalism: A Work in Progress

As we mark fifty years since the adoption of Canada’s federal multiculturalism policy, human rights advocate AMIRA ELGHAWABY celebrates its merits and reflects on the work that is yet to be done when it comes to inclusion, acceptance, and fighting systemic racism in our country.