First, we needed a 4x4 of some sort, along with a driver willing to chance roads that are sometimes passable, sometimes not. The man we found struck us as the quietly skeptical sort, but after a few hundred rutted kilometers, any hesitations he’d been suppressing hardened into emphatic certainties. “The only people who drive on this road,” he told our photographer and me, via our translator, “are people who want to kill their cars.” Yet he gamely pushed ever deeper into Madagascar’s tropical north, until our mud road descended a hill and was swallowed by a wide river. It was the end of the line for the driver. He seemed relieved.

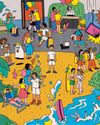

Somewhere on the other side of that water, dozens of farmers would soon converge upon a regional vanilla market in the village of Tanambao Betsivakiny. Growers would negotiate with buyers working on behalf of exporters and international flavoring companies, and together everyone would hash out a collective, per- kilogram price for the crop. Most buyers would pay cash on the spot, and the farmers would hand over several tons of green, freshly harvested vanilla beans.

Those humble beans, whose essence is associated with all that’s bland and unexciting, have somehow metamorphosed, butterfly-style, into the most flamboyantly mercurial commodity on the planet. In the past two decades, cured vanilla beans have been known to fetch almost $600 per kilogram one week, then $20 or so the next. Northeastern Madagascar is the world’s largest producer of natural vanilla, so every boom and every bust slams this region like a tropical storm. When prices peak, cash floods the villages. When prices fall, it drains away.

This story is from the December 23, 2019 edition of Bloomberg Businessweek.

Start your 7-day Magzter GOLD free trial to access thousands of curated premium stories, and 8,500+ magazines and newspapers.

Already a subscriber ? Sign In

This story is from the December 23, 2019 edition of Bloomberg Businessweek.

Start your 7-day Magzter GOLD free trial to access thousands of curated premium stories, and 8,500+ magazines and newspapers.

Already a subscriber? Sign In

Instagram's Founders Say It's Time for a New Social App

The rise of AI and the fall of Twitter could create opportunities for upstarts

Running in Circles

A subscription running shoe program aims to fight footwear waste

What I Learned Working at a Hawaiien Mega-Resort

Nine wild secrets from the staff at Turtle Bay, who have to manage everyone from haughty honeymooners to go-go-dancing golfers.

How Noma Will Blossom In Kyoto

The best restaurant in the world just began its second pop-up in Japan. Here's what's cooking

The Last-Mover Problem

A startup called Sennder is trying to bring an extremely tech-resistant industry into the age of apps

Tick Tock, TikTok

The US thinks the Chinese-owned social media app is a major national security risk. TikTok is running out of ways to avoid a ban

Cleaner Clothing Dye, Made From Bacteria

A UK company produces colors with less water than conventional methods and no toxic chemicals

Pumping Heat in Hamburg

The German port city plans to store hot water underground and bring it up to heat homes in the winter

Sustainability: Calamari's Climate Edge

Squid's ability to flourish in warmer waters makes it fitting for a diet for the changing environment

New Money, New Problems

In Naples, an influx of wealthy is displacing out-of-towners lower-income workers