A year ago, on Friday, March 13, about 50 government officials and experts met for the first time to talk about a crucial problem: how to test more Americans to determine if they were infected with the novel coronavirus. Jared Kushner stopped by; Mike Pence made an appearance later that weekend. SARS-CoV-2 had spread to more than a hundred countries—Tom Hanks had been infected in Australia—and the death toll in the U.S. was expected to reach as high as 250,000. Offices, schools, and streets were emptying; stocks were plunging. The NBA had just suspended its season. It was the official start of the global pandemic.

Admiral Brett Giroir, then an assistant secretary for health at the Department of Health and Human Services, had been put in charge of testing, and he had plenty of concerns. But on that afternoon he was mostly concerned about one essential component of the testing process: swabs. Specifically, the particular 6-inch swab flexible enough to sweep the depths of the nasopharynx where the corona virus replicates, the one now known as the brain tickler, and the only one approved for testing for such respiratory viruses. The U.S. had enough of them to conduct about 8,000 tests a day. That was short by three orders of magnitude—the U.S. needed to do millions of tests a day. Kushner told the admiral to secure a billion swabs however he could and then left.

This story is from the March 22, 2021 edition of Bloomberg Businessweek.

Start your 7-day Magzter GOLD free trial to access thousands of curated premium stories, and 8,500+ magazines and newspapers.

Already a subscriber ? Sign In

This story is from the March 22, 2021 edition of Bloomberg Businessweek.

Start your 7-day Magzter GOLD free trial to access thousands of curated premium stories, and 8,500+ magazines and newspapers.

Already a subscriber? Sign In

Instagram's Founders Say It's Time for a New Social App

The rise of AI and the fall of Twitter could create opportunities for upstarts

Running in Circles

A subscription running shoe program aims to fight footwear waste

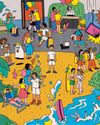

What I Learned Working at a Hawaiien Mega-Resort

Nine wild secrets from the staff at Turtle Bay, who have to manage everyone from haughty honeymooners to go-go-dancing golfers.

How Noma Will Blossom In Kyoto

The best restaurant in the world just began its second pop-up in Japan. Here's what's cooking

The Last-Mover Problem

A startup called Sennder is trying to bring an extremely tech-resistant industry into the age of apps

Tick Tock, TikTok

The US thinks the Chinese-owned social media app is a major national security risk. TikTok is running out of ways to avoid a ban

Cleaner Clothing Dye, Made From Bacteria

A UK company produces colors with less water than conventional methods and no toxic chemicals

Pumping Heat in Hamburg

The German port city plans to store hot water underground and bring it up to heat homes in the winter

Sustainability: Calamari's Climate Edge

Squid's ability to flourish in warmer waters makes it fitting for a diet for the changing environment

New Money, New Problems

In Naples, an influx of wealthy is displacing out-of-towners lower-income workers